Reversing - Bakunawa

In this post we’ll look at another crackme, Bakunawa!

This one was listed as level 5 (Very Hard) and certainly was not without its difficulties!

Featuring a sort-of virtual machine executing real x86 instructions encoded into an odd binary file as a point of obsfucation, this took me quite a long time to figure out. I built some tools in the process and finally a Keygen program once the algorithm was identified and reversed.

Major spoilers follow, here’s the link if you want to have a go yourself!

Tools used today are x64dbg, PEStudio, IDA Pro, F# and C++

First Impressions

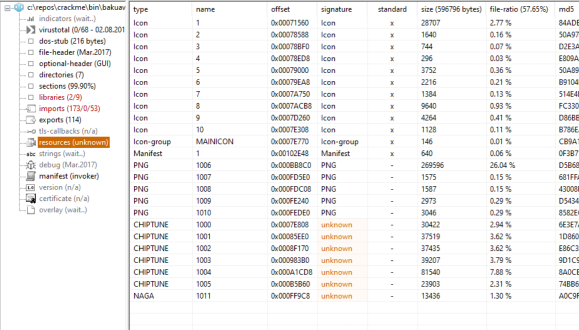

PE Studio identfiies the executable as a normal, non-packed Windows program. Poking around a bit we can see it was compiled with C++ 8 and uses some abnormal libraries such as DirectSound and Winmm.

Looking at the resources (consuming 57% of the executable size) we can see a bunch of images, that appear to be music files, and a rather large binary file called “naga”. We’ll dump this binary to file now since it looks like it will be important.

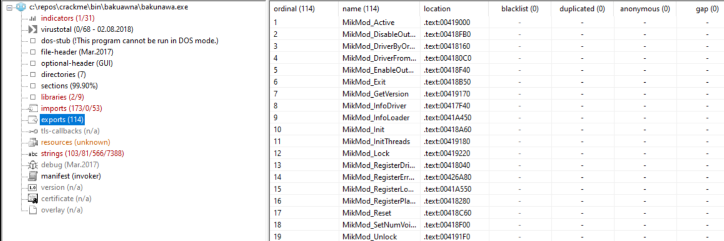

Moving onto imports / exports it seems to have statically linked the MilkMod library so it seems we can indeed expect some music.

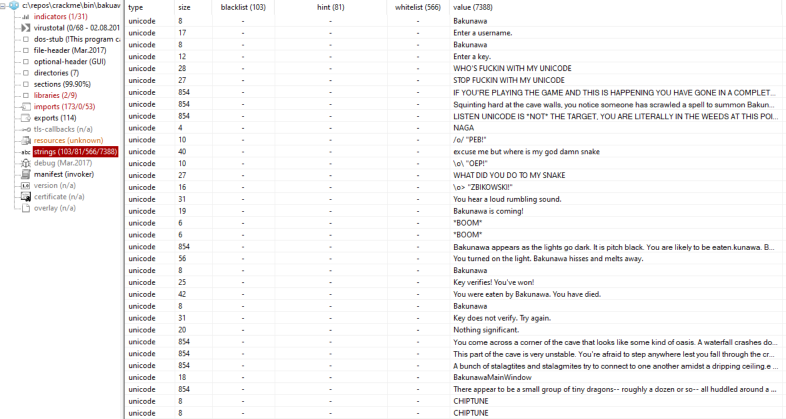

Having a quick look over the strings reveals some fun looking bits, almost like a choose-your-own-adventure!

Fire it up

Running the executable we are presented with a very cool key entry screen accompanied by some great chiptune music.

If you run it with the debugger attached, however, you do not get the screen and instead it plays a chiptune version of The Birdie Song, which is hilairious. Only a RickRoll would have been better!

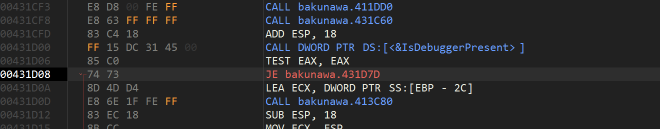

A quick brekapoint on IsDebuggerPresent leads to a simple check which when bypassed, enters a Windows event loop and launches the UI as normal.

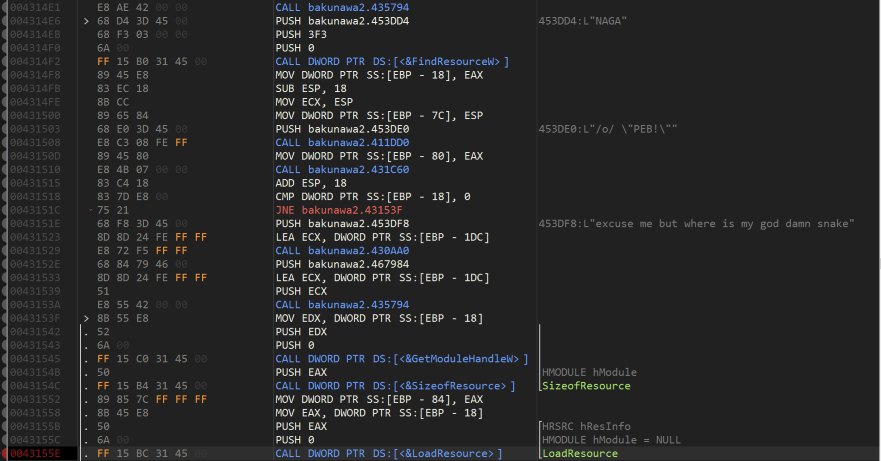

Next up is to find where it is reading the username and password. I’m expecting it’s going to load the mysterious Naga resource at some point as well, so perhaps a good starting place is to put breakpoints on the Windows LoadResource function and see what comes up.

As expected, after a name and password is set and the Verify button is pressed, it attempts to load the resource “Naga” as seen above.

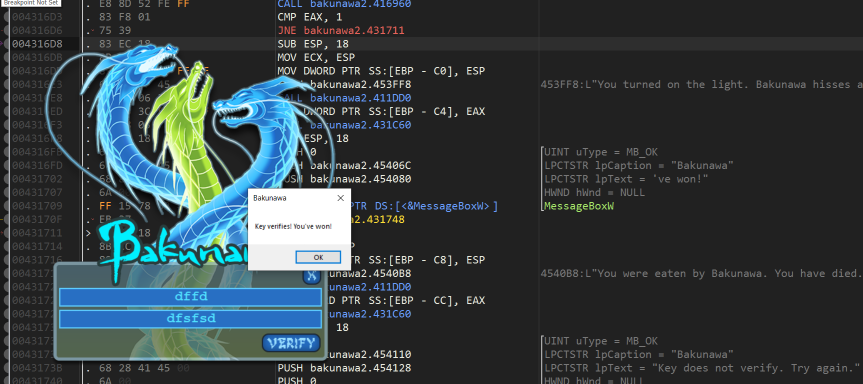

At this stage it’s easy to trace through the code and simply bypass the final check that happens

That’s not much fun, let’s try and work out how the serial check works and build a keygen for it.

Enter The Dragon

There’s quite a lot of stuff happening in this main function. After quite some analysis, two procedures stand out in particular. The first is a function that loads the Naga resource, and has a ton of code that parses the data into structures / classes. We’ll come back to that..

The second is where the magic happens.

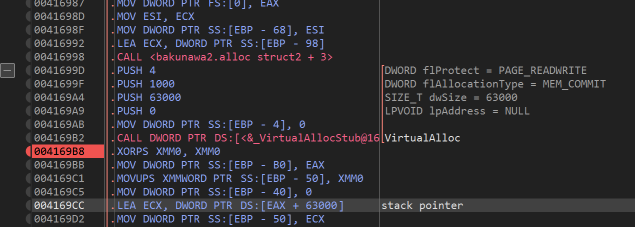

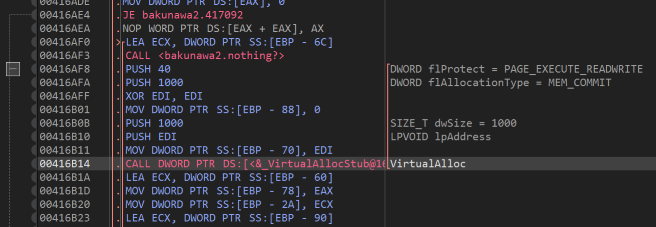

After a bunch of stuff, several calls to VirtualAlloc happen. The first is a large section of read/write memory. After it has been allocated, a pointer is stored to the bottom of the memory. Shortly it will transpire that this area of memory is to be used as the CPU stack. The program will copy a pointer to the username and password that was entered into the bottom of this stack area.

A little further on we see more calls to VirtualAlloc, which have execute permissions. If we poke around in this code for a bit we will see that this area of memory has x86 code copied in to it, presumably from the structures read in from the Naga file. However, it only ever executes small pieces of code at any one time. A clever bit of design here essentially backs up all the CPU registers and moves the CPU stack pointer to the virtual stack location, restoring them at the end of the snippet. In this way it behaves much like a thread does.

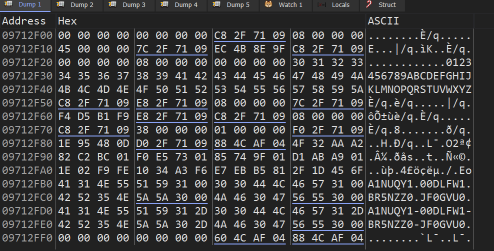

However, because it only executes small bits of code at a time, it is very hard to see what it is actually doing. We can however wait for it to finish processing instructions and have a look at the resulting stack area to reveal some interesting infromation

here we can see it has created some kind of alphabet to use in its keygen, and we can see what looks to be a generated serial in the lower part of the memory. Let’s try this serial in the program and see what happens:

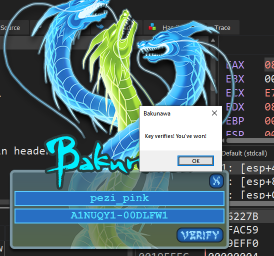

As suspected, it is indeed the serial (though it needed the - character added). Perhaps we won’t need to understand the entire virtual program if we can work out what it’s doing in this last part.

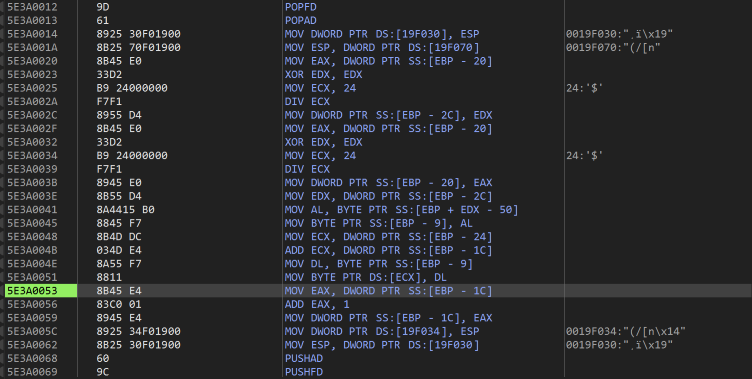

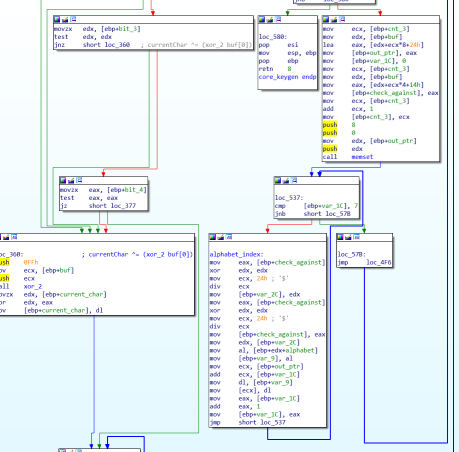

Since we know the area of memory that the serial is written to (as an offset from the virtual stack) then during debugging, after we know the stack location, we can setup a hardware breakpoint to trigger when that location is written to. Doing this and having it trigger a few times leads to this tasty looking morsel.

It looks like we have struck gold here. Analysing this code shows that is divides some value and uses the remainder to index into the alphabet that is used to write the next serial value. Unfortunately, this is only one iteration of the loop, and after a few iterations the mysterious number changes completely. We are not going to be able to write a keygen without knowing where those numbers are coming from.

How to Train Your Dragon

We need to be able to see the entire virtual program. To do so means we are going to have to reverse engineer and understand this mysterious binary file format that holds the machine code in it. Having observed the virtual machine’s behaviour, it is also apparent it knows where Call instructions are and some other bits and bobs. Time to roll up the sleeves and get reversing…

Many hours of work later reveal something like following structure which we can parse in F#

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

let naga = File.ReadAllBytes "c:/repos/crackme/bin/bakuawna/naga.dump"

let inline printHex x = printfn "%X" x

let getByte index = naga.[index]

let getBytei index = uint32 naga.[index]

let getInt index =

(getBytei index) ||| (getBytei (index + 1) <<< 8)

||| (getBytei (index + 2) <<< 16) ||| (getBytei (index + 3) <<< 24)

let getIntw index = uint64 (getInt index)

let getWord index = ((getIntw index)) ||| (getIntw (index + 4) <<< 32)

let startId = getWord 9 // first instruction id stored in header

let numIns = getInt 5 // 515 total instructions

type Dest =

| Jump of uint64

| Call of uint64

type Instruction = {

id: uint64 // ID of this isntruction

nid : uint64 option // pointer to next instruction

len : byte // amount of opcode data

opcodes : byte array// opcode data

dest: Dest option // call or jump target

}

|

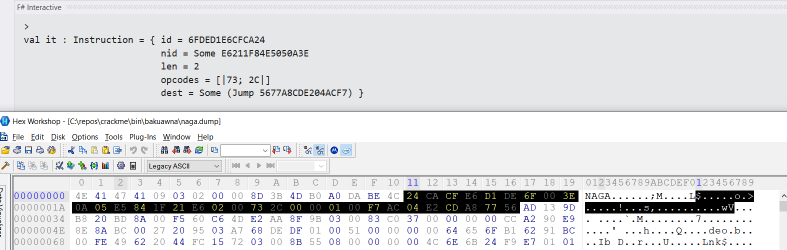

It seems each individual instruction is encoded with a unique ID, the ID of the next instruction, and some extra data that says if the instruction is a jump or call, and if so, the ID of the instruction it routes to. The actual x86 opcode data for the instruction and its operands are encoded directly.

The header has a magic number and some other useless bits, the only relevant parts are the starting instruction id and the total instruction count.

There’s a bunch of other code that creates linked lists of all the nodes and strings it all together. There are four such lists in the core of the program that the machine uses; I don’t know exactly how since it’s far too much to look at it all, but I think this is enough warm up F# and have a go at parsing the data.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

let rawInstructions =

let mutable index = 0x11

seq {

for _ in 0.. (int numIns) - 1 do

let id = getWord index

index <- index + 8

let nid = getWord index

index <- index + 8

let len = getByte index

index <- index + 2 // len is 16 bits but second byte is always blank

let ocs = [|for x in 0 .. int (len - 1uy) do

let b = getByte index

index <- index + 1

yield b |]

let isCall = getByte index

index <- index + 2 // 16 bit as above

let data =

if isCall > 0uy then

let data = getWord index

index <- index + 8

Some (Call data)

else None

let isJump = getByte index

index <- index + 2 // 16 bit as above

if isJump > 0uy && isCall > 0uy then failwith "!"

let data =

if isJump > 0uy then

let data = getWord index

index <- index + 8

Some (Jump data)

else data

yield {

id = id

nid = if nid = 0UL then None else Some nid

len = len

opcodes = ocs

dest = data

}

} |> Seq.toList

let instructionMap =

rawInstructions

|> List.map(fun r -> r.id, r)

|> Map.ofList

|

Here you can see a the first extracted record alongside the binary dump

Performing some analysis on the parsed data reveals some useful information

- There are 8 distinct subroutine calls (unique IDs pointed to by instructions marked as Call)

- The entrypoint is its own subroutine, so 9 in total

- All of the Call instructions use the same opcode / addressing mode of

E8(near, relative) - All of the Jump instructions have relative offsets already encoded and presumably stay in-procedure

- There are several different jump and conditional jump opcodes, with 1, 5 and 6 operands

To produce the working program we’ll have to decide on a memory layout for it. Some of the Call instructions have large relative offsets which would not work with an entry point at location 0x0, so we’ll need to re-write their relative offsets with a location we decide on. We could do the same with the jumps, but it’s best to keep them with their currently encoded targets if possible. That means we will need to parse and understand their relative offset addresses in order to write the target code at the correct place in memory.

First then is to decide where each subroutine will sit in the memory space. To do this we’ll need to know the size of each. To calculate the size, we’ll need to recusrively follow the next pointers, storing any jump targets along the way. Once we are out of instructions, recursively repeat the process on the collected jump targets. It is possible for more than one jump to target the same instruction so we’ll need to make sure they are only visited once.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

let subs = // 8 subroutines

rawInstructions

|> List.choose(fun i -> match i.dest with Some(Call dest) -> Some dest | _ -> None)

|> List.distinct

|> List.map (fun i -> instructionMap.[i])

let collectFullInstructions rootInstruction =

// navigate all "next" pointers

// for jumps, add their destinations to the list resursively

let seen = System.Collections.Generic.HashSet<uint64>()

let rec aux instr jumps collected =

if seen.Contains instr.id then

match jumps with

| h :: t -> aux h t collected

| [] -> collected

else

let jumps =

match instr.dest with

| Some(Jump dest) -> instructionMap.[dest] :: jumps

| _ -> jumps

seen.Add instr.id |> ignore

match instr.nid, jumps with

| Some nid, _ ->

aux (instructionMap.[nid]) jumps (instr :: collected)

| None, h :: t ->

aux h t (instr :: collected)

| _ -> collected

aux rootInstruction [] []

let rootLen =

let i = instructionMap.[startId]

i, collectFullInstructions i |> List.sumBy(fun i -> int32 i.len)

let subLens =

subs |> List.map (fun i -> i, collectFullInstructions i |> List.sumBy(fun i -> int32 i.len))

|

With the lengths calculated, we can assign them starting memory locations, with a little bit of blank space between each.

1 2 3 4 5 |

let programLayout =

((0,[]), rootLen :: subLens)

||> List.fold(fun (last,res) (instr, subLen) -> last + subLen + 10, (last, instr) :: res ) |> snd

|> List.map(fun (addr,i) -> i.id, addr)

|> Map.ofList

|

This creates a map indexed by the starting instruction id that we can use when assembling.

We need a way or parsing the jump target opcodes so we can calculate their position in memory

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

let getJumpOffset instr =

match instr.opcodes.Length with

| 2 -> int32 (sbyte instr.opcodes.[1])

| 5 -> // 5 len jmp, operand in last 4 bytes

((0,0),instr.opcodes.[1..])

||> Seq.fold(fun (i,tot) oc -> (i+1,tot ||| (((int32 oc) <<< i * 8)))) |> snd

| 6 -> // 6 len jnb, operand in last 4 bytes

((0,0),instr.opcodes.[2..])

||> Seq.fold(fun (i,tot) oc -> (i+1,tot ||| (((int32 oc) <<< i * 8)))) |> snd

|

Have to be careful with this stuff, it’s easy to get tripped up with signed and unsigned data. It is important in the preceeding code that the result is treated as signed, since we’ll be using it to re-calcuate addresses and we need negative numbers to work properly.

Finally we are left with the task of writing the assembler itself, which will

- Create an array of bytes for the resulting program

- For each subroutine in our memory layout ..

- Change the instruction pointer to our subroutine location

- Follow the instruction trail, writing the relevant opcode bytes into the array

- When we hit a Call, we must calculate the new relative offset from where we are to the location of the routine from our memory map

- When we hit a Jump, we must parse its operands and calculate where it should be assembled, then add it to the “to be assembled” list like we did when calculating the subroutine lengths earlier

- Don’t assemble jumps more than once

Here’s the fist version I got working, a lovely mix of mutable and immutable code that I’m sure purists everywhere will approve of

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 |

let assemble() =

let program = Array.create (0x1000) 0uy

let seen = System.Collections.Generic.HashSet<uint64>()

let mutable eip = 0

let copyBytes arr =

for b in arr do

program.[eip] <- b

eip <- eip + 1

let rec aux list =

match list with

| (addr,instr) :: rest ->

eip <- addr

// recursively assemble via nip

// collect any jump targets along the way,

// and rewrite Call targets

let rec aux2 instr targets =

let targets =

match instr.dest with

| Some(Jump dest) ->

if seen.Contains dest then targets

else

seen.Add dest |> ignore

// calculate where this jump ends up.

let offset2 = getJumpOffset instr

let finalOffset = offset2 + (int32 instr.len)

(eip + finalOffset, instructionMap.[dest]) :: targets

| Some(Call dest) -> // use this branch for side-effect only, lovely!

let target = programLayout.[dest]

let current = eip + (int32 instr.len)

let offset = target - current

// write call target into the opcode data

instr.opcodes.[1] <- byte (offset &&& 0xFF)

instr.opcodes.[2] <- byte ((offset >>> 8) &&& 0xFF)

instr.opcodes.[3] <- byte ((offset >>> 16) &&& 0xFF)

instr.opcodes.[4] <- byte ((offset >>> 24) &&& 0xFF)

targets

| _ -> targets

copyBytes instr.opcodes

match instr.nid with

| Some nip -> aux2 instructionMap.[nip] targets

| None -> targets

let targets = aux2 instr rest

aux targets

| [] -> []

for kvp in programLayout do

aux [kvp.Value,instructionMap.[kvp.Key]] |> ignore

program

|

Now we can write out the array as a binary file and we should have the fully re-constructed virtual program that we can disassemble and reverse engineer.

Dragon Masters

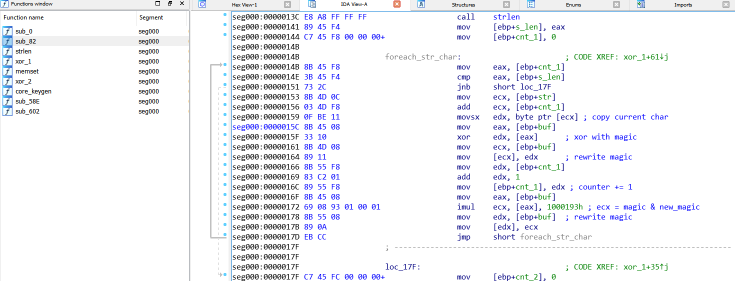

IDA Pro sucessfully disassembles the program ready for static analysis. It’s about 500 lines or so of assembler code.

Here we can see some of functions after they have been analysed and renamed. You can see I found strlen and memset equivalents, along with a few functions xor1 and xor2 that are called in various ways before core_keygen does the work of actually producing the serial.

It is way too much to show here of course (please ask if you are interested!) but here’s the piece of code we saw earlier where it was indexing into the alphabet, with some of its surrounding code.

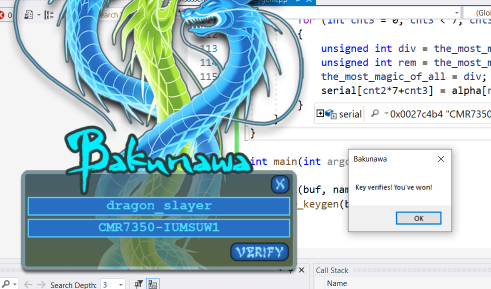

I won’t explain how the algorithm works exactly. Rather I have re-written the core of it, somewhat different since I have no need to programmatically generate the alphabet and such things. It is in C/C++ of course since it far easier to write all this very unsafe pointer stuff and bitwise manipulations.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 |

const char * name = "dragon_slayer";

unsigned char buf[0x44];

unsigned char serial[0x24];

const int magic = 0x811C9DC5;

const int magic2 = 0x1000193;

const int magic3 = 0x7FFFFFFF;

unsigned int things1[4];

unsigned int things2[4];

char alpha[36] =

{ '0','1','2','3','4','5','6','7','8','9',

'A','B','C','D','E','F','G','H','I',

'J','K','L','M','N','O','P','Q','R',

'S','T','U','V','W','X','Y','Z' };

int xor2(int magic, unsigned int* buf)

{

int d = buf[0] / magic;

int r = buf[0] % magic;

int x = buf[0];

buf[0] = _rotl(buf[0],0x10); // ROL 10

buf[0] ^= r;

buf[0] *= magic2;

return r;

}

void xor1(unsigned char* buf, const char* str)

{

memset(buf, 0, 0x44);

unsigned int* ptr = (unsigned int*)buf;

*ptr = magic;

int nameLen = strlen(name);

for (int cnt1 = 0; cnt1 < nameLen; cnt1++)

{

*ptr ^= str[cnt1];

*ptr *= magic2;

}

for (int cnt1 = 0; cnt1 < 4 ; cnt1++)

{

int rem = xor2(magic2, (unsigned int*)buf);

rem += magic2;

things1[cnt1] = rem;

rem = xor2(magic3, (unsigned int*)buf);

rem += magic3;

things2[cnt1] = rem;

}

}

void core_keygen(unsigned char* buf, const char* name)

{

int nameLen = strlen(name);

for (int cnt1 = 0; cnt1 < nameLen; cnt1++)

{

unsigned char c = name[cnt1];

char bit1 = c & 0x1;

char bit2 = c & 0x2;

char bit3 = c & 0x4;

char bit4 = c & 0x8;

char bit5 = c & 0x10;

char bit6 = c & 0x20;

char bit7 = c & 0x40;

if (bit1 || bit2 || bit3 || bit4 )

{

c ^= (xor2(0xFF, (unsigned int*)buf));

}

for (int cnt2 = 0; cnt2 < 4; cnt2++)

{

if (bit1)

{

things2[cnt2] += (c ^ xor2(0xFF, (unsigned int*)buf));

}

if (bit2)

{

things2[cnt2] -= (c ^ (xor2(0xFF, (unsigned int*)buf)));

}

if(bit3)

{

things2[cnt2] ^= (c ^ (xor2(0xFF, (unsigned int*)buf)));

}

if (bit4)

{

things2[cnt2] |= (c ^ (xor2(0xFF, (unsigned int*)buf)));

}

if (bit5)

{

things2[cnt2] += c;

}

if (bit6)

{

things2[cnt2] -= c;

}

if (bit7)

{

things2[cnt2] ^= c;

}

}

for (int cnt2 = 0; cnt2 < 4; cnt2++)

{

things2[cnt2] *= things1[cnt2];

}

}

for (int cnt2 = 0; cnt2 < 2; cnt2++)

{

unsigned int the_most_magic_of_all = things2[cnt2];

for (int cnt3 = 0; cnt3 < 7; cnt3++)

{

unsigned int div = the_most_magic_of_all / 0x24;

unsigned int rem = the_most_magic_of_all % 0x24;

the_most_magic_of_all = div;

serial[cnt2*7+cnt3] = alpha[rem];

}

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

xor1(buf, name);

core_keygen(buf, name);

}

|

Once this program has finished, it leaves the calucalted serial in serial[] Bakunawa execpts it to be entered in two parts separated by a - character. Let’s try it!

Conclusion

This was a very cool crackme that obviously had a great deal of time spent designing and writing it. It took me a couple of solid days’ work plus a few smaller sessions to finally achieve the end goal of writing and testing it. Most of the time was spent trying to understand the binary format. Thanks to Frank2 for writing it. It also includes several very cool chiptune tracks, though I was quite sick of them in the end and worked out which thread I needed to suspend to stop them from playing all the time!